What is Public History? A Slam Poem Ode by an "Intro to PH" Undergraduate

Every time I teach Intro to Public History, we begin the semester with two sets of readings. One set examines public history as it is situated within:

The other set? Classics like Becker's "Everyman His Own Historian," David Lowenthal's meditation on the benefits and burdens of the past, Pierre Nora's famous (and famously dense) discussion of lieux de memoire, "sites" both literal and metaphorical that serve as bridges between history and memory and as anchors of identity in a rapidly changing and homogenizing world.

************

- the history of the national parks

- the discipline of history

- the context of efforts to amplify invisible, untended or uncomfortable histories

- the context of ordinary people's interests and engagements with the past

These go over very well.

These go over terribly. And I assign them anyway.

This semester, I made my students do a reading response to these readings. Some of them were fabulous. Some of them, shall we say, reflected the complexity of the texts. And there was this. A first. A slam poem reflection on history, memory and public history from the smart and thoughtful Dan McGuire.

Here you go:

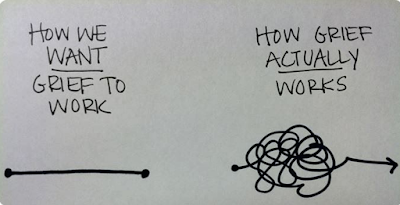

Memory moves: its commonplace fog flows from the forefront to a fastidious fin within a fortnight or few. Moments pass, but alas, so do facts. Herein lies the cause for historical intrigue: subjectivity abounds in interpersonal circles and shifts asunder blunders of remembrance, careless and oft-falsified grandeur in lieu of pithy wonder – the truth. Yet if the personal pains the platitudes of memory, the collective projects the final blow. Intellectuals carve while communities starve, competing for the final morsels of meaty memoranda. Ivory towers block the root notes (local history and communal scholarship) from keeping the beat for the books and brains to selfishly solo on top. Intellectual rot reeks of egoists bloviating into oblivion while ‘armchair’ agitators muck the moors of modern mental matriculation. Such claims decry graduate falsehoods: advanced degrees bring advanced understanding. Nonsense. The public deserves better. They deserve academics devoid of the pomp and pressures of publishing. They deserve driven, dutiful people focused on finding out what truly happened. They deserve public historians!

Treading water gets tiring right quick. Stick a historian in water and they’ll sink or get sick. Swimmers feel the burn and simply turn. Historians have muscular eyes instead of toned triceps to dive. But they tire. Reading renders the reader a simple purveyor of anything the writer wishes. If he chooses to devote an entire chapter to existential undertones in Olympic water-polo so be it, the reader must obey. He might become annoyed and think – “how could this writer have chosen such high-minded nonsense instead of getting to the real meat of the game?” The question therein signals the most important aspect of historical study: picking what to study, why, and which sources (primary and secondary) to utilize. Professional historians more often than not pick peer’s work to prove points. They stay immersed in their archives and libraries to the point of exhaustion. When one stumbles out of their House of Letters they might find, spray painted on the wall before them, a mural. It might depict a recent riot or a once-local figure now nudged into the national: whatever the case, books and essays can only show a part of the puzzle. The people those scribbles of lexigraphy represent truly matter, not decades-removed pretense a la post-Pulitzer pleasure. People are in the game for the game and not for the people.************

OK. Is it just me? Or does it seem as if he was just waiting for the vocabulary to talk about history, memory and the public? About telling stories that matter? About the problems with academic history?

Another public historian is born! (And this was published with his permission. Albeit blushingly.)

Comments

Post a Comment