The Politics of Remembrance in Northern Ireland

I have been thinking about the Troubles for fifteen years, researching and trying to tell histories of nationalists in Derry, Northern Ireland for ten. As a result, many people have asked me what I think of the the recent news cycle, featuring Sinn Féin's Gerry Adams, murdered Belfast widow Jean McConville and the Police Service of Northern Ireland.

My response has been a vague, "I think it's complicated." There has been a rash of whataboutery out there, to which I am loathe to add even a syllable ( -- from Martin McGuinness's comment about the "dark forces" in the PSNI, Northern Ireland's police force to the lachrymose recapitulations of the abduction and murder of McConville, a widowed mother of 10 accused of passing information to the British army whose body was missing until 2003 -- that sounds like "republicans are all evil" masquerading as sympathy for McConville's children.)

There has also been intelligent and thoughtful discussion -- if you are interested in learning more or trying to understand issues of memory, victimhood and the Troubles, I recommend Susan McKay's piece in The Guardian and Brian Walker's short op-ed on the Slugger O'Toole online journal.

The longer answer to what I am thinking? Adams' arrest reminds me how high the stakes remain, how much memory matters, how abiding is the tendency to wield the past in the name of contemporary politics in Northern Ireland. Mostly, I am struck by how exhausted people are by this process -- exhausted by their pain and others', by choreographies of violence in public that don't serve healing, by inconclusive efforts to "deal with the past," by the struggle of quilting together a collected memory* of the last forty years that does not privilege some stories, some people, and erase others in the name of a shared remembrance of the Troubles.

Many, from all corners of the political map, concur that the anemic effort to address the legacies of the Troubles means that the "residue of the past" can never go away - at least not for long. Walker and McKay, veterans of the Northern Ireland beat, voice a wearied urgency, or maybe an urgent weariness.

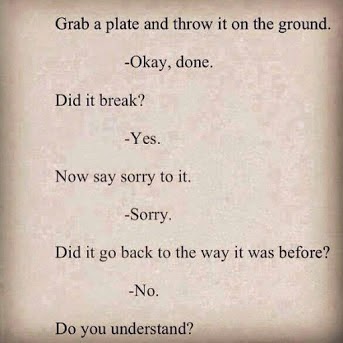

They, along with The Boston Globe's Kevin Cullen come back to the same point --- 16 years after the Good Friday agreement (and Omagh,) there is no consensus in Northern Ireland about who the victims are, who the perpetrators are, and how publicly to acknowledge, attribute blame, accept apology or move on from the past. Slugger O'Toole editor Mike Fealty posted this little tutorial, which sums up the problem nicely:

But the thing is --- in public, the debate over who broke the plate remains. Kathryn Stone, who is stepping down after eighteen months as Northern Ireland's victims' commissioner, noted last week, "I came here to advocate for all victims and survivors. People, however, want to know whose side you are on. My answer always has been that I am on the side of victims and survivors. In this place it is as simple and as complicated as that."

I notice there's been a renewed call to initiate the Haass plan of a truth and reconciliation commission, or "a commission for information retrieval;" the plan was shelved last December because Northern politicians would not get behind it. Through this process, those coming forward voluntarily with information related to violence associated with the Troubles would receive some measure of immunity.

Calls for truth and reconciliation commissions are sometimes rooted in a misplaced faith in the therapeutic benefits of recounting violent memories in public. I think many in Northern Ireland have found this generally to be painful, re-traumatizing and unhelpful, even counterproductive. Healing, as McKay points out, is not linear. It happens in the privacy of our hearts and in the complex terrain of our family environments. And yet, there remains some sense that public processes are prerequisites for private ones.

So, perhaps the pundits are right. In order for a new politics, born out of a new vision of both the future and the past, to grow and thrive -- it is time for some honest truth-telling from the police, republicans who have embraced a way forward that doesn't include armed struggle, the British army, the loyalist paramilitaries.

It is time to defang the past in public and to mix metaphors, to slop slinging it around in the face of each new election, parading season, etc.

Only then can families, communities and individuals come to terms with the Troubles' legacies in their own lives. At the same time, I think it is critical, and difficult, to address Geraldine Finucane's thoughtful point that healing is not a wholesale process. "You have to look at what you are healing. Everything needs healing in a different fashion...."

People do not, and perhaps cannot, agree on how the events of the Troubles should be remembered. That's the clincher, really, that divides the process of remembrance. And that is what needs to become central to the process of remembrance.

*The idea of collected memory is the genius of James Young, explored in his book The Texture of Memory.

My response has been a vague, "I think it's complicated." There has been a rash of whataboutery out there, to which I am loathe to add even a syllable ( -- from Martin McGuinness's comment about the "dark forces" in the PSNI, Northern Ireland's police force to the lachrymose recapitulations of the abduction and murder of McConville, a widowed mother of 10 accused of passing information to the British army whose body was missing until 2003 -- that sounds like "republicans are all evil" masquerading as sympathy for McConville's children.)

There has also been intelligent and thoughtful discussion -- if you are interested in learning more or trying to understand issues of memory, victimhood and the Troubles, I recommend Susan McKay's piece in The Guardian and Brian Walker's short op-ed on the Slugger O'Toole online journal.

The longer answer to what I am thinking? Adams' arrest reminds me how high the stakes remain, how much memory matters, how abiding is the tendency to wield the past in the name of contemporary politics in Northern Ireland. Mostly, I am struck by how exhausted people are by this process -- exhausted by their pain and others', by choreographies of violence in public that don't serve healing, by inconclusive efforts to "deal with the past," by the struggle of quilting together a collected memory* of the last forty years that does not privilege some stories, some people, and erase others in the name of a shared remembrance of the Troubles.

Many, from all corners of the political map, concur that the anemic effort to address the legacies of the Troubles means that the "residue of the past" can never go away - at least not for long. Walker and McKay, veterans of the Northern Ireland beat, voice a wearied urgency, or maybe an urgent weariness.

They, along with The Boston Globe's Kevin Cullen come back to the same point --- 16 years after the Good Friday agreement (and Omagh,) there is no consensus in Northern Ireland about who the victims are, who the perpetrators are, and how publicly to acknowledge, attribute blame, accept apology or move on from the past. Slugger O'Toole editor Mike Fealty posted this little tutorial, which sums up the problem nicely:

But the thing is --- in public, the debate over who broke the plate remains. Kathryn Stone, who is stepping down after eighteen months as Northern Ireland's victims' commissioner, noted last week, "I came here to advocate for all victims and survivors. People, however, want to know whose side you are on. My answer always has been that I am on the side of victims and survivors. In this place it is as simple and as complicated as that."

I notice there's been a renewed call to initiate the Haass plan of a truth and reconciliation commission, or "a commission for information retrieval;" the plan was shelved last December because Northern politicians would not get behind it. Through this process, those coming forward voluntarily with information related to violence associated with the Troubles would receive some measure of immunity.

Calls for truth and reconciliation commissions are sometimes rooted in a misplaced faith in the therapeutic benefits of recounting violent memories in public. I think many in Northern Ireland have found this generally to be painful, re-traumatizing and unhelpful, even counterproductive. Healing, as McKay points out, is not linear. It happens in the privacy of our hearts and in the complex terrain of our family environments. And yet, there remains some sense that public processes are prerequisites for private ones.

So, perhaps the pundits are right. In order for a new politics, born out of a new vision of both the future and the past, to grow and thrive -- it is time for some honest truth-telling from the police, republicans who have embraced a way forward that doesn't include armed struggle, the British army, the loyalist paramilitaries.

It is time to defang the past in public and to mix metaphors, to slop slinging it around in the face of each new election, parading season, etc.

Only then can families, communities and individuals come to terms with the Troubles' legacies in their own lives. At the same time, I think it is critical, and difficult, to address Geraldine Finucane's thoughtful point that healing is not a wholesale process. "You have to look at what you are healing. Everything needs healing in a different fashion...."

People do not, and perhaps cannot, agree on how the events of the Troubles should be remembered. That's the clincher, really, that divides the process of remembrance. And that is what needs to become central to the process of remembrance.

*The idea of collected memory is the genius of James Young, explored in his book The Texture of Memory.

Comments

Post a Comment